- Home

- Laura Dockrill

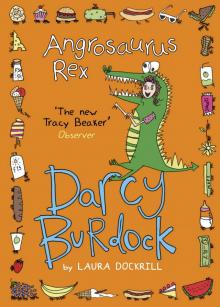

Darcy Burdock, Book 2 Page 2

Darcy Burdock, Book 2 Read online

Page 2

Lay the bread out on a chopping board. Make sure the chopping board is not actually a trap door that will make your bread fall through otherwise you will lose sight of your bread for eternity.

Butter the bread.

Stack up ingredients in a tasty order. TIP: place ingredients in an order that makes it appear to others that you are exclusively the only chef in the whole world that could possibly know what order to make this in (but really this doesn’t matter).

The best way to enjoy is to start chewing and even if it’s not to your taste, still pretend it’s gorgeous to the outside world, who will never know otherwise. Which actually is also an excellent tip for life itself.

And I quote . . .

‘The best way to enjoy life is to start chewing and even if it’s not to your taste, still pretend it’s gorgeous to the outside world, who will never know otherwise.’

All right, me making up a saying. I am proud of my own self.

The Mighty Sandwich is absolutely gross. Dad drives us to the fish and chip shop where we get two massive pillows of family-sized chips drenched in vinegar and salt which was excellent amounts of enjoyable. But Mum ruined the whole experience because she felt guilty that we wasted so much food on our Mighty Sandwiches and so tomorrow we have to take all our books to the charity shop at the end of the road to ‘give back’.

I love my mum; everybody knows you can’t eat books!

Chapter Three

Later, when I’m sat on the sofa watching television with everyone, I find myself worrying about Big School again and want to tell my brain to behave. When I was younger I wanted a comfort blanket so badly. Did you know, although you may have found this out the hard way, the same rules apply for comfort blankets as they do nicknames . . . you don’t get to pick them yourselves. Like a nickname, a comfort blanket must find you.

I was never given a bit of blanket to cuddle or a label to flick or a silkie to stroke or a bobble to gobble – Mum said those kids were annoying, always carrying a dirty old square of material or bit of T-shirt around with them – but it didn’t stop me wanting one. One day when Mum was throwing out the old curtains, I dramatically threw myself onto this one end of curtain, pretending I had a real ‘connection’ to it and eventually after much deliberation and annoyance (from Mum’s part) she allowed me to rip off a weary bedraggled rag. And this rag soon became my ‘comfort blanket’.

Next was the name. All comfort blankets needed a name so that when you referred to them only you and those close knew what you were on about. That’s the whole point. It’s an attention-seeking thing, a bit like an imaginary friend.

I tried.

Bam-Bam?

No.

Wonky?

Yuck.

Binky? Bong-Bong?

Stupid and babyish.

Huggy?

Too obvious.

And then it hit me. CUF-CUF. This was going to be my CUF-CUF.

CUF-CUF would be my only true real actual friend that I would whisper all my secrets into the cottoned ear of. And she would listen and whisper back, probably even she would make me do stuff like insist on eating a series of midnight feasts and snap Poppy’s dollies legs off and I’d have to obey, of course. We were bound to have lots of fun together, this comfort blanket and I.

It turned out that CUF-CUF didn’t make a very good friend after all because she didn’t do much comforting or whispering and so I got bored of CUF-CUF after a while. It was just one of those things I didn’t really need, it turns out. I guess the more olderer you become in life the more your interests change and so do your (big word alert) priorities. A priority means the main things you care about more than other things. Like for example, if I sit down to eat a roast dinner my priority is the roast potatoes rather than the broccoli. Well, when I was smaller my priorities were:

Wondering why they hardly ever make trousers for dollies.

Pretending to own a shoe shop.

Pretending to talk on the phone.

Overdosing from a sugar overload.

Lying completely still to convincingly look like I was dead.

But now my priority is my family.

As we sit all cuddled up, one on top of the other, bellies full from our chips, Lamb-Beth snoozing on our laps, the air shifts from normal to cold but it doesn’t touch us; our dozing heads, our holding hands, our floppy socks. I want to stay here in this moment for ever, like a tiny frozen snowflake. Never growing up. Never going to biggerer school. Never, never, never.

Chapter Four

Grandma is staying with us for a bit – she always does when Dad has to work away from home. It’s like she and Dad can’t be in the same place at the same time . . . maybe Grandma is actually Dad dressed up as a grandma? Oh my goodness! No. That would be stupid – funny, but mainly stupid.

It is cold today, ouch cold. Summer has been officially stolen. So cold the air is fizzing whizzing spinning white particles that are like snow but not as fun or as good because they are not living properly, they are just dissolving like not-ready ice cubes in Coca-Cola. It is ‘biting’, Grandma says as she wobbles us through the high street, nipping us from shop to shop. Mum’s got a cold and is in bed, cough cough cough. It is NOT September weather. It’s all everybody talks about. The weather is what you’re meant to talk about with people that you don’t have much in common with; I’ve been learning this off my grandma. The clouds are fat with rain tears and the pigeons are flapping about all livid and everybody’s skin is cracked and scaly like a snake.

We are getting medicine for Mum in the chemist. I’m looking at the packets of hair dye, all those girls with all that shiny slippery hair, so brushed. It flips my belly. I want to dye my hair blue but Grandma won’t let me. If I must start big school, it would be cool to do it with blue hair. The chemist smells of seashells and mint and, oddly, a bit like smoky bacon.

Back out in the cold again.

Every part of my body is freezing cold for freezing cold’s sake, so cold I can’t breathe. And the wind is lashing tears out of our eyes that make us all look like we are crying. Where is the summer? The sky is a cold concrete grey, moody and marbly and giving away no secrets. The puddles are deep. Each tree stands like the open claw of a frightening creature, naked and charcoaled and worrying me.

Put some clothes on, trees. Keep warm, I am thinking.

It’s sprinkling rain but it’s too windy to have our umbrellas up so instead we have to get cold and wet and unhappy. Plus Grandma’s walking pace is basically this – a slug.

Who on earth does this weather think it is?

When we get back indoors, Grandma shouts, ‘Halllllllooooooo!’ up the stairs and then slams her hand over her mouth when she remembers Mum must be sleeping. ‘Crumbs!’ she says as she ushers us in the house, muttering at us to keep quiet, followed by lots of ‘oh dear, oh dear’ and various other mumbling-under-breath terms.

Dad is away for work with silly John Pincher, like I told you, so the house is major messy because he is the one who does most of the tidying. There are little dots in the carpet from Lamb-Beth’s moulting speckled fur fluff . . . technically that is actually my job to clean but it’s boring so I don’t often get round to that one.

‘Get the kettle on, love,’ Grandma says to me as she unzips Hector’s coat, struggling and complaining about the cold and the chill and the bite and the freeze and how numb her hands are and how she can’t feel a thing. I feel sorry and sad when I see the wrinkled skin on her dainty fingers as they work on Hector’s fiddly toggles, and his bright little pink nose is leaking two clear gooey lines of snot. Like space jelly. Uck.

Hmmmmmm. Hmmmmmm. Hmmmmmm. I’m thinking as I’m waiting for the kettle to boil. I’ve been allowed to make tea for only a couple of months now and Grandma is seriously taking advantage of this – she uses language to make it seem like making tea is easy, like:

‘TIP me out a tea, would you, dear?’

Or:

‘POP the kettle on, would you, love?

’

Or:

‘NIP in the kitchen and POUR us out a cuppa.’

These words such as TIP and POP and NIP and POUR do not demonstrate the actual physical and technical skill involved in making a cup of tea.

Hmmmmm.

Poppy is still not allowed to make tea because of the hot water in case she burns herself. A friend of a friend of a friend that I know has no belly any more because of burning herself with hot water. She actually has a big space in the middle of her body, so you do have to be so careful.

I get two teaspoons and pretend I am in a band whilst I’m waiting for the kettle to boil. I drum the spoons on the sugar pot, the coffee pot, the tea bag pot and the milk. The kettle noise is the bass.

‘Aw, you, my Darcy, should win the best granddaughter in the world award,’ Grandma cheers as I careful-gently carry her teacup in its tinkering saucer.

They should start a ‘Best Granddaughter in the World Award’ – I could have a decent shot at winning that. I am pretty good.

I sit down next to her and rest my head on her shoulder. I think about sneaking upstairs and seeing Mum but Grandma says she is sleeping.

Then a little white envelope plops through the letter box with ‘Darcy and Poppy’ written on the front in shaky ugly hand lettering. Mysterious, I think, and shout Poppy’s name, before getting told off by Grandma for making too much noise.

We nestle down on the sofa, fighting over the corners, and together, sort-of-ish, rip open the envelope and two packets of sunflower seeds fall out all over our laps with a little card:

* * *

Thank you for my card with the sunflower on the front, here are some seeds to plant some sunflowers of your own.

From Cyril,

your next door neighbour.

* * *

We both look towards the window: on the pavement outside, a woman’s umbrella folds itself inside out in a gust of wind and Poppy looks as though she is about to cry. I don’t think I would like to be born in this weather if I was a sunflower. I put the seeds on the side and decide we should wait for that fashionably late sun to show its stupid face. If it ever will again.

Chapter Five

They were big. They were ugly. They were wretched and horrid and reminded me mostly of every single worst thing in the world.

My new school shoes.

I HATE them, I am thinking, but can I say this? NO.

WHY not? Because Grandma chose them.

‘What about the clogs?’ I cry.

‘They didn’t have any backs to them.’ Grandma reaches for her purse.

‘The . . . trainers?’ I try desperately.

‘Don’t be silly.’

‘The panda-bear sandals?’

‘They are for infants.’

‘The high-heel ones?’

‘Don’t be so repulsive.’

They CAN’T be my shoes. They can’t be anybody’s shoes! They clearly are a factory malfunction major mistake that somebody got fired for. Or a prank. My eyes fill with water as we leave the shop, the woman waving us out and probably shaking her head thinking to herself, What a pair of idiots, knowing that nobody would ever buy themselves such ghastly footwear. Then again, what else should I have expected, letting an ancient antique come shoe-shopping with me? It’s my own entire miserable fault.

Poppy thinks the whole thing is

H-I-L-A-R-I-O-U-S.

And my depression has given her some kind of new energy, which is managing to make her skip crazily down the street in absolute smug joy. I think about throwing one of the shoes heftily at her back but am frightened that the shoe is that heavy it could quite possibly kill her. So I resist.

‘They are very practical.’ Grandma smirks delightfully proudly over our stop-off for tea, and Poppy laughs her head off.

‘Yeah, practical for running away from all the bullies,’ she says. She does actually have a point.

The shoebox sits under my bed like a coffin. It matches the prison garments that I am expected to wear with them. How on earth am I meant to show off my dazzling personality in all that gross grey? When I got ‘accepted’ at the school I clearly recall Mum saying, ‘You will love the uniform.’ And I remember thinking, Unless it is the same uniform amazing people get to wear when they are doing nothing except having fun and not being scared, then I don’t want to wear it. But I don’t have One. Single. Choice. It is hideous. Grey and like sewage. I can’t bear it.

‘Let’s see you then, monkey.’ Mum’s eyes peel open wide, making all this going-to-Big-School thing a massive chunky deal.

‘I hate the uniform, Mum,’ I growl.

‘I can’t do anything about that, love, plus once you’re there you’ll forget all about it because everybody will be wearing the same thing.’

‘Well, you could do something about these shoes, surely?’ I kick one of the shoes into the wall.

‘Don’t do that, Darcy, you’ll scuff them!’ Mum squeaks. ‘And look at the wall.’ She tuts and licks her thumb and rubs the wall like a lizard but it makes the mark a bit bigger. She breathes through her nose which means she’s ‘on the brink’ (basically going mad).

‘Good. I want to scuff them. Not the wall. These shoes,’ I moan to get back onto the shoe topic. ‘They are ugly and big and all . . . dompy.’

Mum laughs. ‘What did you call them?’

‘Dompy.’

She likes it. She laughs. ‘Dompy. I see what you mean. They are sort of . . . dompy.’

‘See?’ I begin to laugh too.

‘Why don’t you write a story about these . . . dompies? You never know, it might convince you to like them . . . just a little?’

‘I doubt it.’

I line the shoes up on the kitchen table and stare at their brown leather and ugly buckle. I flick open my writing book and begin . . .

Have you ever heard of a new and tiresome beast called ‘the Dompy’? No?

Of course you have not, Over-Keen One, because I just made it up.

Well, this beast is the most ridiculous creature ever. They look like a large shoe. They are brown. They have skin like an elephant. They have a beak like a platypus, eyes like beetles and a mouth like an upturned horse hoof. Their ears are tiny. The species of Dompy is very almost impossible amounts of rare. The Dompy is a lonely and feeling-sorry-for-itself type of creature, who finds being alive quite tough. The most recognizable and unique feature of the Dompy is its oversized hunchback that is full of Dompy worries. The Dompy’s worries are really full of silly made-up things that aren’t even true – like ‘everybody hates me because of my ugly hunchback’ – but all that happens by the Dompy worrying about his ugly hunchback is that the hunchback just gets bigger, then the Dompy will start to worry about the hunch getting bigger which then just only goes on to make the hunch even bigger and then he worries about that, which then makes the hunch on his back bigger and makes him sadder and lonelier and grumpier and all the while the hunch grows and his confidence shrinks.

The Dompy felt so fed up. Sometimes he would stare at his lonesome reflection in the lake and let the ripples of the water surface take his hunchback away for a second, but it never worked, it was just an illusion. He would look on at the other spring-footed, light-speed-whipping mammals parading around, frolicking and rolling and hopping and jumping, and then back at his reflection and he would think, Why me? and the hunch would grow another bunch.

‘There’s nothing wrong with you, mate,’ Toad ribbitted. ‘Look at my chin, it goes on for miles, look at my warts, they’re horrible things but it’s what makes me who I am.’

‘Easy for you to say, you’ve got plenty of friends who love you for who you are,’ the Dompy grunted sulkily.

‘Well, maybe if you stopped whining and whingeing so much, you’d have more friends,’ Toad snubbed.

‘Well, maybe if I had MORE friends, I wouldn’t NEED to whine and whinge!’ the Dompy protested.

Then out of the reeds came the charcoal-coloured Bully Cat. He

was big and gruff and sniffed and snuffed and spat but was the most respected and powerful beast on the planet. He had come to sip from the lake.

‘Good afternoon, Bully Cat,’ Toad croaked, tidying around his little corner of lily pad as though Bully Cat had entered his home to inspect it.

‘Good afternoon, Toad,’ Bully Cat purred.

Toad nodded to the Dompy, signalling him to greet Bully Cat, and as nervous as he was after his little pep talk with Toad, the Dompy did as he was advised.

‘Good afternoon, Bully Cat.’

And Bully Cat finished drinking from the lake, sniffed, snuffed, swallowed and spat and slid away from the lake, ignoring the Dompy completely and the Dompy’s hunch grew a bunch.

‘Oh no – my hunch, look it’s even bigger – What did I do wrong, Toad? I don’t understand.’ The Dompy wanted to cry.

‘Me neither,’ Toad sympathized, ‘but let’s not give up yet, we can always say good afternoon to somebody else and see if they will be your friend.’

‘I don’t think I can take any more rejection today,’ the Dompy cried.

‘Don’t be silly,’ Toad reassured. ‘Bully Cat is difficult to impress . . . look, there’s Panda Paw, he’s friends with everybody, he will certainly say good afternoon and want to make friends with you.’

‘Do you think so?’ The Dompy looked at his feet. ‘I do like the sound of being mates with Panda Paw.’

Toad hopped over to Panda Paw who was sleepily lazing under a tree.

‘Good afternoon, Panda Paw! Wakey wakey!’ Toad croaked.

‘Ah, good afternoon, Toad, lovely to see you.’ Panda Paw yawned a great yawn and stretched.

Toad winked at the Dompy, who did as he was told and managed to gurgle out, ‘Good afternoon, Panda Paw!’ before waiting for the warm reply. But instead he just heard snores coming from Panda Paw’s nostrils. ‘He didn’t even notice me!’ the Dompy cried as his hunch grew a bunch.

Big Bones

Big Bones Lorali

Lorali My Ideal Boyfriend Is a Croissant

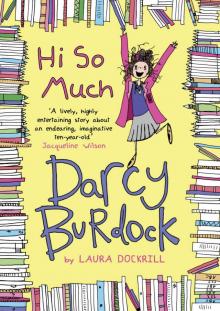

My Ideal Boyfriend Is a Croissant Darcy Burdock Book 3

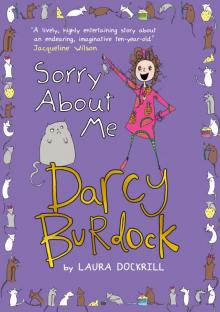

Darcy Burdock Book 3 Darcy Burdock

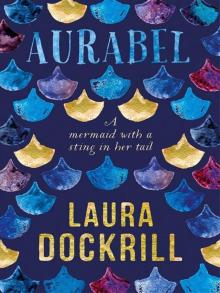

Darcy Burdock Aurabel

Aurabel Darcy Burdock, Book 2

Darcy Burdock, Book 2